This article was published in

Anaesthesia Newsletter May 2003

In Shock and Awe………………A letter from UgandaDr.Ray Towey FRCA was a consultant in Guy's Hospital London, has worked for the past 10 years in East Africa and is currently working in northern Uganda.

Africa has a great capacity to put you into both shock and awe so as I write this letter from St.Mary's Hospital Lacor in Gulu northern Uganda forgive me for borrowing the sound bite from the US military planners for we here are also in a war zone in more ways than one. The real enemy in our situation is poverty, poverty of medicines, equipment, infrastructure, trained personnel, management and the poverty is indeed shocking. However what is awesome is the capacity of our staff and especially my African colleagues to cope with these deprivations and with amazing good humour to actually deliver a high standard of medical and surgical care, much cherished by the local community. In another way we are also in a war zone in that there has been a war continuing in northern Uganda for over 15 years and road ambushes by rebel troops are a weekly occurrence. This is not a high tech. war. There are no B-52 carpet bombing payloads or cruise missiles or weapons of mass destruction, (or should I say weapons of mass injury/murder), but for the local population being killed or injured by a AK 47, a rocket propelled grenade or landmine, all by the way imported from the so called "developed" world at a handsome profit, is just as devastating as being hit by high tech. killing systems. For us in the hospital the sense of security is good, that is while we remain in the hospital. Travelling is another story.

We care for both the government and the rebel injured and probably most importantly because the local mission in the person of Brother Elio will give a decent burial to any fatal rebel casualty, as an institution we have not been a target. This is awesome in a conflict that has defied almost all moral bounds in its cruelty. Last week in our ICU we had the incongruous sight of one rebel soldier lying next to one government soldier. The professional response of the staff to treat all injured the same is exemplary and yes it is awesome when you consider how much the local people have suffered in this conflict. We are about 4 hours driving distance from the capital, Kampala, on a tarred road. In my analysis I divide the world into three areas, the rich northern countries, the capital cities of the so-called developing world, and the rural areas of the developing world. In short we are in the final category, in some ways the final frontier. In my time I have worked in all three areas and each has its own stresses not to be minimised. We are a five theatre suite and we have the capacity to work all five at any one time though this is unusual. With so little resources how do we manage that? In a nutshell skilled dedicated staff and appropriate technology. Many anaesthetists are technophiles and I plead guilty. This article will reach you via the Internet by way of a radio modem and a modified boosted GSM type mobile phone. This connectivity from our location continues to amaze me. It is indeed a small world though much divided.

Our anaesthetic practice is founded on spinal blocks and draw over ether and halothane. It is hard to know what we would have done without the EMO and OMV vaporisers made by Penlon in Abingdon. If there is any Penlon staff out there, many thanks ! A supply of oxygen is always a concern for the rural practitioner and our hospital uses both oxygen concentrators and cylinders. Our paediatric ward has the capacity to treat 16 children using DeVilbiss oxygen concentrators with flow splitters and this frees up the cylinders for theatre use. Many thanks to Sunrise Medical, Wollaston, in the West Midlands ! Hopefully this year we will also have oxygen concentrators for theatre and we then anticipate a major reduction in oxygen cylinder usage in the hospital. As we can only obtain cylinders from Kampala, a journey not undertaken lightly, a move to oxygen concentrators will be much appreciated. To see this appropriate technology making a substantial contribution to the patient care in this remote area is a most satisfying experience. I think it would be fair to say that our anaesthetists can give very good conditions for almost all surgical procedures with our basic equipment. Of course we have limitations. It is appalling to see a patient in theatre with a ruptured uterus because she has been in labour for two days having had no access to any analgesia or any proper care transferred from a more remote area, or to watch someone bleed to death because we have no fresh frozen plasma or platelets, or to walk away from a patient dying from respiratory failure because our capacity to ventilate is limited to just a few hours.

Probably the most appalling example of inequity is the knowledge that a large proportion of our patients are HIV positive but cannot afford treatment. The shocking truth is that profit for the so-called "developed" world comes before life giving treatment for the rest. The national debt of Uganda is about $4 billion and each year $50 million is still being paid back to western banks in debt repayments. It continues to amaze me that most Africans have so little bitterness in the face of this appalling inequity. When $780 billion per year is spent on the world's armed forces, $17 billion on pet food in Europe, I have to ask, why is Africa still paying debt repayments and has almost no anti-retroviral drugs? In global terms this amount of debt is small change but for our patients it is a life to death change, so if you could help me with an answer to that question I would truly be in shock and awe.

Ray Towey

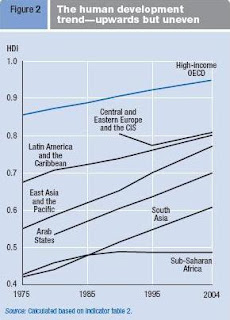

Life expectancy improving every where except sub-Saharan Africa !! From 2005 Human Development Report. chapter 1, page 19

Life expectancy improving every where except sub-Saharan Africa !! From 2005 Human Development Report. chapter 1, page 19

.JPG)

The Human Development Index produced by the UN is a measure of quality of life. It includes life expectancy, education, literacy, and financial resources of the average individual in that country. The closer to the number 1 the better the quality of life. For sub-Saharan Africa the index has not improved since 1985 while in virtually the rest of the world it is going up at great speed. The health care and education in Africa is tantamount to a crime against humanity. This graph was taken from the Human Development Report of the UN 2006. page 265

The Human Development Index produced by the UN is a measure of quality of life. It includes life expectancy, education, literacy, and financial resources of the average individual in that country. The closer to the number 1 the better the quality of life. For sub-Saharan Africa the index has not improved since 1985 while in virtually the rest of the world it is going up at great speed. The health care and education in Africa is tantamount to a crime against humanity. This graph was taken from the Human Development Report of the UN 2006. page 265